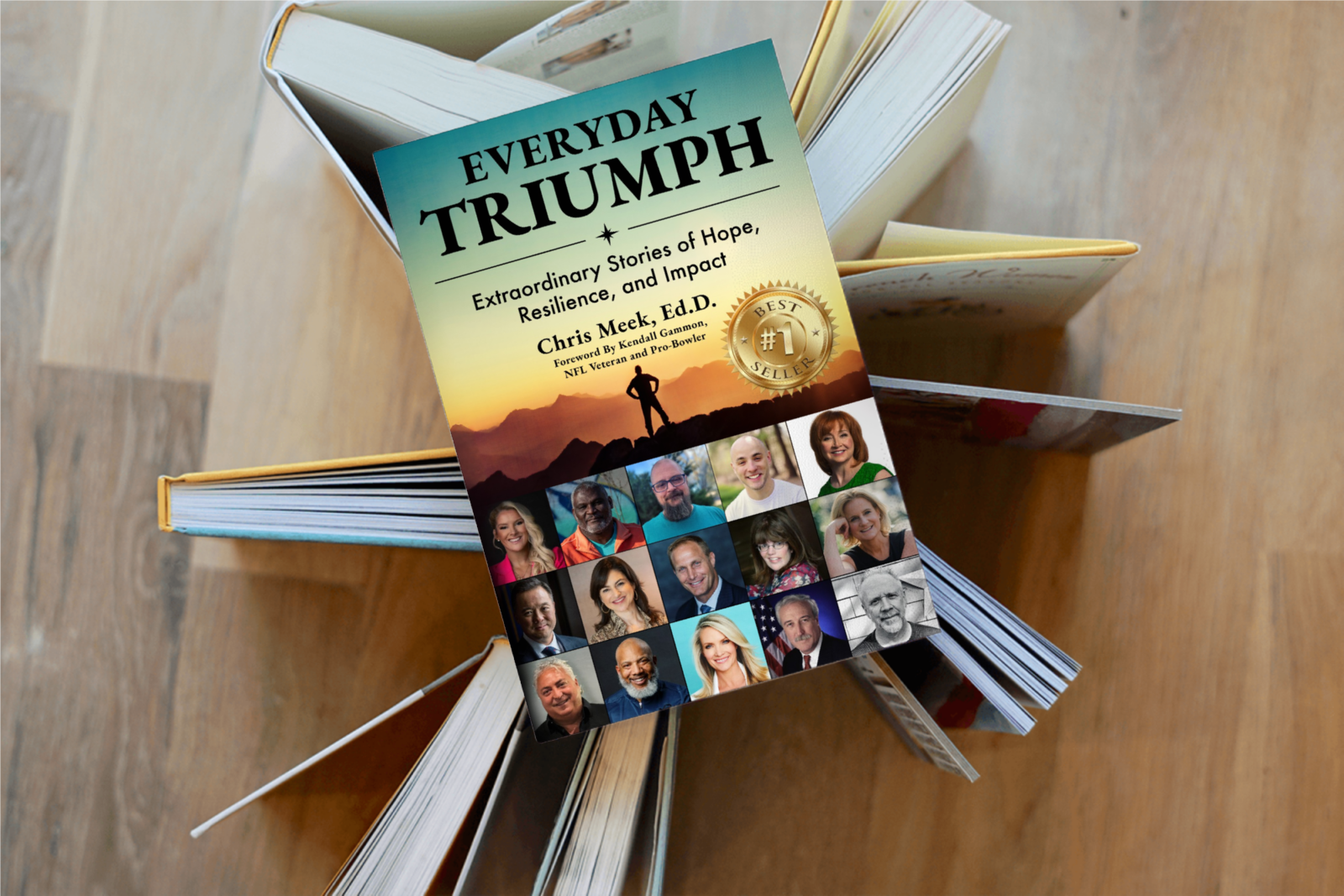

Please enjoy the introduction of my newly released book “Everyday Triumph”:

The American journalist, novelist, and political activist Katherine Anne Porter once wrote, “Who wants to read about success? It is the early struggle which makes a good story.”

I disagree. Struggle without success more often than not leaves us bruised, disheartened, hollow, and bitter. With apologies to the late Ms. Porter, success is a crucial ingredient to a good story.

How many times have we heard that Americans love a second act? Do we remember the runner who falls down, gets up, and finishes second? No. Instead, we cheer for the fallen competitor who gets up and passes all the other runners to win the race.

Success tells us there was a purpose for our toil and travails, and that the struggle was worth it. Success inspires us at least as much, if not more, than the struggle. Success matters.

The stories in the chapters ahead are of men and women who have struggled, been resilient, and made their unique impacts on the world around them.

As a Ground Zero survivor of the horrendous terror attacks of September 11, 2001, that claimed the lives of 2,606 people at the World Trade Center towers and another 390 people when hijacked flights crashed into the Pentagon and near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, I feel a connection to each and every one of them. On that day and many days that followed, I witnessed acts of courage, determination, rage, anguish, defiance, and despair. Every human emotion imaginable was on display in the minutes and hours after those two jets struck the Twin Towers as toxic debris filled the air, choking our lungs and searing our eyes.

The sights and sounds on such a massive scale are still overwhelming. That day left an indelible scar on my soul and psyche, just as it certainly did on everyone who was there and millions across the world who stopped and stared in stunned silence at the countless number of televisions and computer screens that were tuned to the nonstop coverage of the carnage.

Long before that day I had occasionally pondered words that have been repeated infinite times. I have no doubt that every single day someone, somewhere—typically a newscaster—utters something about an “ordinary person” performing an extraordinary act of kindness or courage. And I’ve wondered, Was she really just “ordinary,” or was this act truly extraordinary? After all, the first words that usually follow the ordinary/extraordinary declaration are from the hero insisting, “I only did what anyone else would have done.”

Is our ordinariness—or extraordinary status—determined by nothing more than random timing and events? If someone would have leapt into action to catch a child who fell from a five-story window but they just happened to be a block away, does that mean they’re ordinary? If we changed places with the people who did save the child’s life, would they be any less extraordinary, even though they played no role in the rescue in the second scenario?

These thoughts came back to my mind as I thought about the men and women I intended to highlight in this book. And every time the discussion rolled around to the “ordinary people doing extraordinary feats” theme, I felt as if I’d run into a brick wall.

There is no way that I would consider a single one of the people whose stories are told in the chapters ahead as being “ordinary.” Many are either friends through our shared commitment to a cause, such as the national nonprofit SoldierStrong, which I cofounded in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, or they’ve become friends while appearing on my VoiceAmerica – Live Internet Talk Radio podcast, Next Steps Forward with Dr. Chris Meek. And all of them are extraordinary.

I was left to ponder again: What does that say about the rest of us?

Ultimately, I recognized a simple fact. We are all extraordinary in our own way. We simply have to let ourselves shine—and push ourselves, sometimes far beyond our self-imposed limits, to reach our full potential.

That is exactly what the people in the pages ahead have done, although I’m certain, too, that part of their success was their ability to recognize far sooner than most that they did not have to accept the limits that hold back so many others.

In the chapter about Sylvie Légère, cofounder of The Policy Circle, I write about an expression my mother repeatedly told me when I was growing up: “We might not be able to change the world today, but we can change the world around us.”

My parents divorced when I was two and my mother raised me on her own until my father re-entered my life in my early teens.

A story in the December 19, 1979, edition of the Elmira Star-Gazette detailed how my mom took six deaf students on an early Christmas trip to New York City because, she’s quoted as saying, “there’s more to education than the three Rs . . . especially if your students can’t hear.”1

The article continues: “The trip was planned for a year but Camille ended up spending hundreds of her own dollars to pull it off. A second-year teacher earns about $10,000 a year. And she worked a long time to get that kind of money. Camille, 29, received her bachelor’s degree in speech and hearing from Elmira College after 10 years of intermittent study. She started at Corning Community College but that was interrupted by marriage and the birth of her son, Christopher, now 9. Divorced, Camille and son live with her parents on W. Washington Ave.”

It mentions how the students sold candy and pens, and my mom wrote to service clubs to ask for donations. In New York City, the article states, “They visited the Statue of Liberty, Chinatown, the Empire State Building and all those other tourist places. They saw the Christmas Show at Radio City Music Hall. They ate their meals out. The last was at the Top of the Sixes, which is 80-plus stories up overlooking Central Park. The meal cost more than $200 but it was worth it, Camille said. Rides through Central Park in horse-drawn carriages capped the evening.”

The group traveled to the Big Apple in a van, but the two chaperones returned to Elmira alone because my mom wanted the students to have the experience of boarding a flight home.

As the article states, “The trip didn’t have to cost what it did. But as Camille put it: ‘I figured if we were going to go, we’re going to do it right or it’s not worth it.’ The students were lucky. Not every high school student gets a chance to go to the big city.”

The spirit of that trip would be repeated frequently throughout Camille Meek’s career as an educator of students with hearing disabilities. A keen and compassionate observer of others, she recognized that many students were the products of trying, even the most terrible, circumstances. While she made me aware that life doesn’t owe us anything and that even our own unfair circumstances are not unmanageable, my mom took great pains to share the extra kindnesses with her students that so many of us have been blessed to take for granted.

Bringing them home from school with her, she would feed them homemade meals and give them a warm, safe place to sleep.

Again she would tell me, “We might not be able to change the world today, but we can change the world around us.”

The fact is, as Camille Meek was changing the world around her, she did change the rest of the world that day—and many days after too. Those students who had no hope were transformed in ways we’ll never know, simply because she cared. It’s a story that is repeated as Aaron Stark shares the story of his teenage years, when his seemingly inevitable course to violence and destruction was changed by the empathy of another child. Aaron’s friend had no way of knowing it, but his caring very easily may have changed the world as much as it changed the world around him.

Even stories that begin with us taking care of ourselves—such as when four-time All-American track star John Register was forced to recover from a devastating injury, or when Tim McCarthy fought to regain his mental wellness—ultimately result in the world being changed around us.

My mother’s example instilled in me the need—no, the burning desire—to give back. After 9/11 I moved to Connecticut where my wife, Christine, and our family still live. Of course, it’s important to note that I was by no means alone. Many Americans were stirred to give back after that fateful day.

For me, the goal was straightforward: I wanted to empower people. In early 2009, with my background on Wall Street and an economic crisis looming large, I offered my expertise to people facing foreclosures and the agony of losing their homes. The effort gave birth to my first nonprofit, START Now! (Start Taking Action and Responsibility Together), which helped individuals and families achieve financial empowerment through education, support, and opportunities already available to them. It wasn’t the largest or most powerful nonprofit— not even among those focused on mortgage holders—but in the end START Now! helped 252 families over an 11-month period restructure their mortgages so that they avoided foreclosure and kept their homes.

That same year stories abounded that our military men and women fighting the Global War on Terror in the Middle East lacked such basic items as socks, baby wipes, and sunscreen. Friends and family inspired me and others to organize supply collections and fundraising events to get our service members those everyday necessities. Before long my second nonprofit, SoldierSocks, was launched. During the next few years SoldierSocks collected and shipped more than 75,000 pounds of necessities to 73 units overseas.

To change the world around us—or to strive to change the world itself—means we must change ourselves by adapting to emerging realities. As the war scaled down and more service members returned home, we knew that SoldierSocks must change its name and focus. That’s when SoldierStrong took up the mission of connecting wounded veterans to revolutionary technology and educational opportunities to help them take their next steps forward. Again, the goal was to empower people.

Scholarships drove intellectual empowerment

Through the donation of robotic exoskeletons to Veterans Affairs medical centers and other health care facilities across the country, SoldierStrong helped to physically empower paralyzed veterans.

While assisting injured veterans, it soon became evident that a growing mental health crisis was affecting even more veterans. Many suffered the invisible wounds of post-traumatic stress, as an average of 22 veterans were taking their own lives every day. It was only natural that an organization committed to addressing veterans’ most urgent needs would seek solutions to foster mental empowerment. That’s when SoldierStrong began donating virtual reality hardware and software systems, developed by a team at the University of Southern California’s Institute for Creative Technologies, to VA hospitals to treat post-traumatic stress.

I’ve never fought in a war and I know my experiences on 9/11 are different from those who served in uniform, but I do know what it’s like to be forced to confront traumatic memories. (In fact, like many who were in lower Manhattan that day, I have previously been reluctant to call myself a Ground Zero survivor, as I had thought that distinction should be left for the men and women who made it out of the Twin Towers that fateful morning.)

In 2018 I finally returned to Ground Zero and accepted that my experiences that day shared many similarities with the experiences of so many other survivors.

The dreaded sights, sounds, and smells of September 11, 2001, forced their way back into my mind, affecting me physically and emotionally. I lost my mother in those intervening years. She was 56 when she lost her battle with cancer but there was never a doubt that Camille Meek changed the world around her many times over. She also had done so by changing me.

As you read the extraordinary stories of each person featured in the pages ahead, know that you too possess the power to change the world around you each day, and in doing so, you will change yourself for the better too.

To purchase Everyday Triumph, visit Amazon today.